COMPETITION POLLING

(41/50)

1671892049

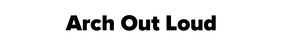

We’ve got this third eye, the eye that comes to us perfectly manufactured with unlimited memory. Our third eye, dependable as it may be, endangers thoughtful engagement with the built environment.

Approaching, entering, and lingering in a space poses the challenge of finding the perfect frame to publish. Or one simply documents it to remember for later. Or one takes a picture with it ‘just to say I was there.’ Or one does not care. The significance of a space is no longer bound to its narrative. Details that fade: how it came to be, why it exists, what it’s made from.

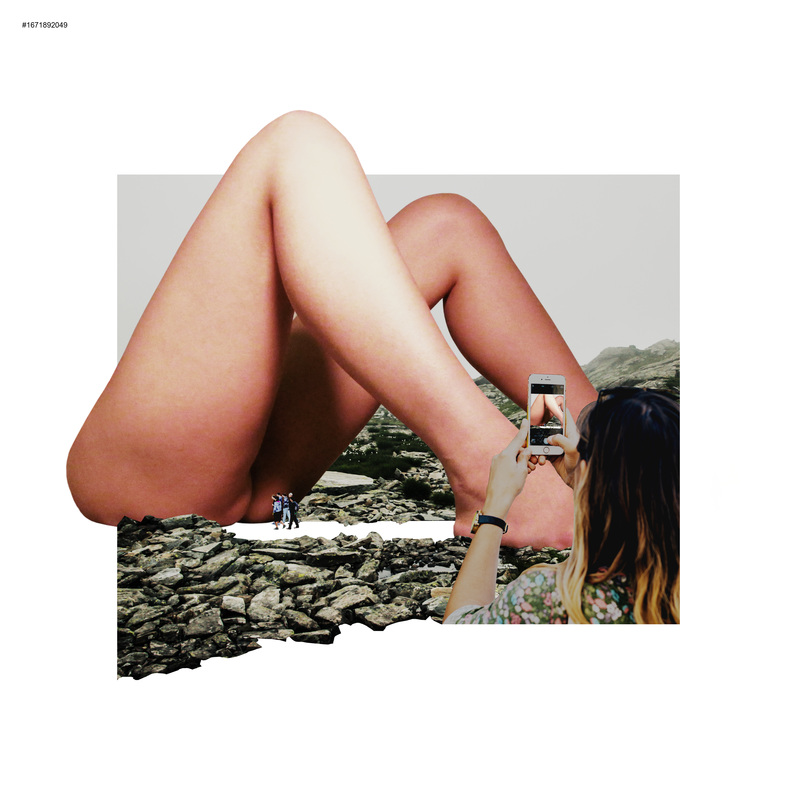

How does the architect, noble champion of the built environment, react? The architect responds to the shifting landscape of memory by crafting accessible images, buildings that can be as easily summarized in the mind as it can be on camera. Indulge people in their deepest desires of accumulating the most social validation. Give them something to talk about by harnessing the most provocative forms of simple objects. The resulting building is not pornographic; rather, it is freed from the elite knowledge of architectural history and context.

A tomato, rotting. A bottle, shattered. A beach ball, deflated. Legs, spread. Embedded in each provocative image, two dimensional or three dimensional, is an implied narrative. Just as geometry undergoes certain mathematical operations in other buildings, this new object-verb typology derives its operations from the identity and properties of the object. Photography’s objectification of buildings proves no longer offensive or inaccurate if a building intends to be an object from the start. To continue the spectacle, the interior becomes a direct translation of the object’s anatomy. Patrons are able to navigate the building based on understandings unrelated to architecture. Visitors of the building shaped like a woman’s loins enter the vaginal chamber to find the cervix, which promises more space beyond its narrow corridor, at the deep end of the vagina. After passing through the cervix, they face a decision in the uterus: to take the left fallopian tube or the right.

The goal is to make spaces that are manageable even with minimal mental processing. Object buildings hold high aesthetic value for its deviation from the traditional architecture trajectory. Iconic and social media-ready, they are destined to be thoroughly documented by un-thorough minds and live down in short-term history.

Perhaps once they’ve left the womb, they will see the world anew.

Approaching, entering, and lingering in a space poses the challenge of finding the perfect frame to publish. Or one simply documents it to remember for later. Or one takes a picture with it ‘just to say I was there.’ Or one does not care. The significance of a space is no longer bound to its narrative. Details that fade: how it came to be, why it exists, what it’s made from.

How does the architect, noble champion of the built environment, react? The architect responds to the shifting landscape of memory by crafting accessible images, buildings that can be as easily summarized in the mind as it can be on camera. Indulge people in their deepest desires of accumulating the most social validation. Give them something to talk about by harnessing the most provocative forms of simple objects. The resulting building is not pornographic; rather, it is freed from the elite knowledge of architectural history and context.

A tomato, rotting. A bottle, shattered. A beach ball, deflated. Legs, spread. Embedded in each provocative image, two dimensional or three dimensional, is an implied narrative. Just as geometry undergoes certain mathematical operations in other buildings, this new object-verb typology derives its operations from the identity and properties of the object. Photography’s objectification of buildings proves no longer offensive or inaccurate if a building intends to be an object from the start. To continue the spectacle, the interior becomes a direct translation of the object’s anatomy. Patrons are able to navigate the building based on understandings unrelated to architecture. Visitors of the building shaped like a woman’s loins enter the vaginal chamber to find the cervix, which promises more space beyond its narrow corridor, at the deep end of the vagina. After passing through the cervix, they face a decision in the uterus: to take the left fallopian tube or the right.

The goal is to make spaces that are manageable even with minimal mental processing. Object buildings hold high aesthetic value for its deviation from the traditional architecture trajectory. Iconic and social media-ready, they are destined to be thoroughly documented by un-thorough minds and live down in short-term history.

Perhaps once they’ve left the womb, they will see the world anew.

(42/50)

1690289210

Three Eyes are Better than Two

Memory is the architecture of the human condition. It acts as a point of reference when deciphering time and space. Memory is the substance of the human soul. It is a mental manifestation of the triumphs and tribulations set over the course of our existence. Memory’s influence on the built environment is profound. Every place, space, and object is factored into the collective human consciousness. This ongoing dialogue between the past and present inform us on where we came from and how we feel about where we are headed.

With the advent of digital technology, the ability to record, transmit and receive information has exponentially expanded. Digital memory allows mankind to automate the monotonous and arbitrary so they can focus on other endeavors. These methods of memory are also scalar in the built environment, some taking priority of importance over others. The presence of this digital memory is unseen, however. We only experience the results of these technologies, yet they have a significant influence in our everyday lives. Digital memory allows humans to put less emphasis on their own memories, but paradoxically be more attune at retrieving and transmitting the collected and shared memories. They can expand human capabilities and are central in almost all of our decisions.

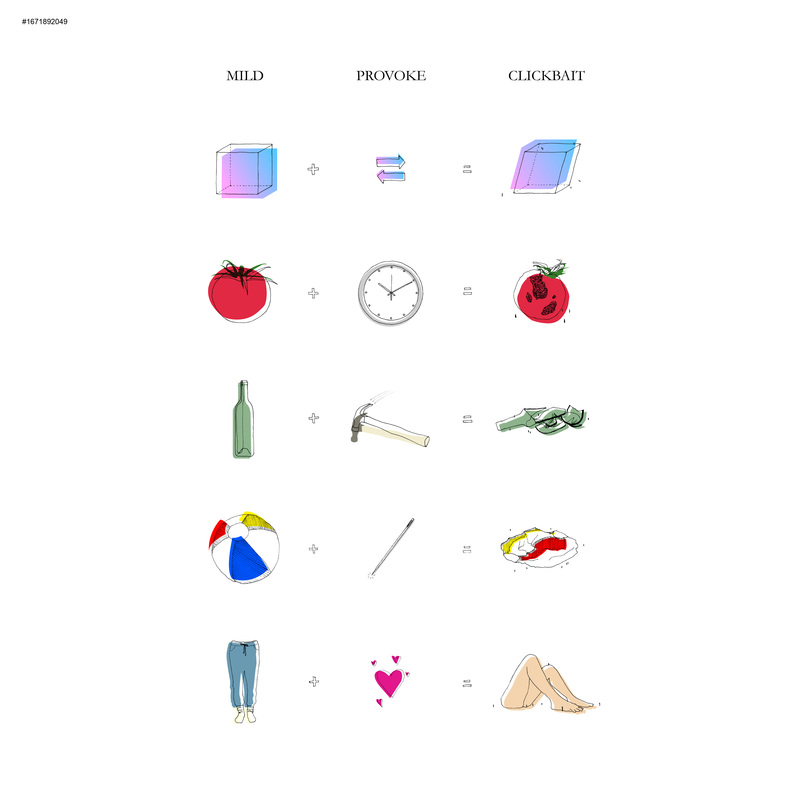

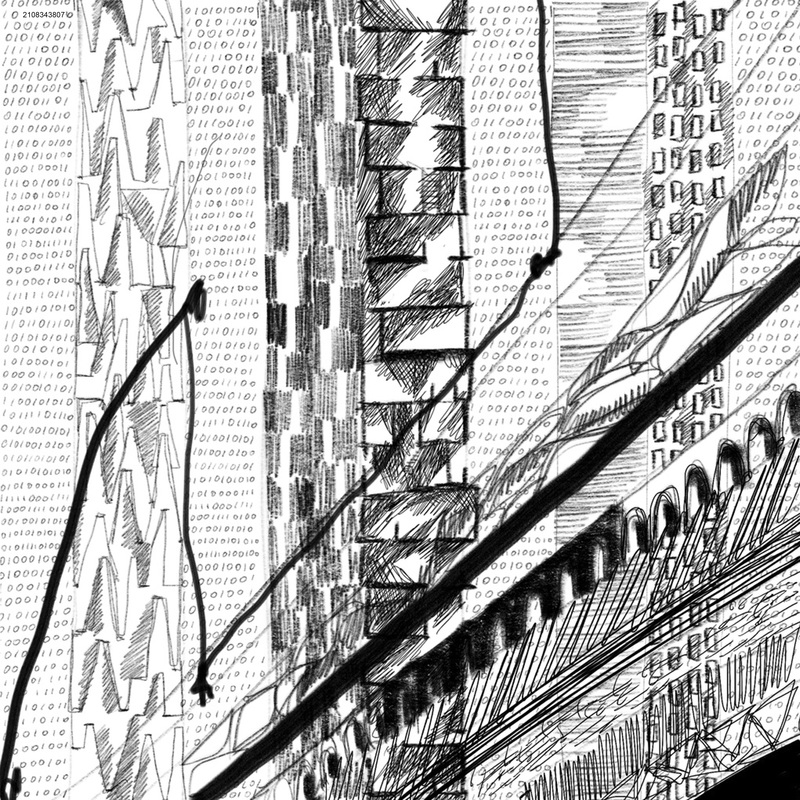

In the second image, digital memory is represented the vacuum of space as a congested network or rigid highways. These digital highways are traversed and intersected by more organic sinuous forms. These organic forms harken back to the diverse nature of human memory. When human memories collide with the digital, they tend to distort and reflect these digital memories outwardly form their own perspective. There is an oversaturation of digital memory in the built environment, but by virtue of its transparency it does overstimulate us. We, in turn, have access to any information whenever and wherever we could ever need it.

The first image represents the transmission of a memory from a person’s head, to the digital dimension. The path that the man is on is one of past and present memories. This Third Eye is constantly sifting through the realm of thought to recollect and remember what is stored along the way. It represents the man himself, and his own view of what he believes is true and absolute. As memories leave the realm of thought into the digital, they become diluted into zeros and ones. As they leave the individual, they no longer belong solely to that person, but to all of us.

Memory is the architecture of the human condition. It acts as a point of reference when deciphering time and space. Memory is the substance of the human soul. It is a mental manifestation of the triumphs and tribulations set over the course of our existence. Memory’s influence on the built environment is profound. Every place, space, and object is factored into the collective human consciousness. This ongoing dialogue between the past and present inform us on where we came from and how we feel about where we are headed.

With the advent of digital technology, the ability to record, transmit and receive information has exponentially expanded. Digital memory allows mankind to automate the monotonous and arbitrary so they can focus on other endeavors. These methods of memory are also scalar in the built environment, some taking priority of importance over others. The presence of this digital memory is unseen, however. We only experience the results of these technologies, yet they have a significant influence in our everyday lives. Digital memory allows humans to put less emphasis on their own memories, but paradoxically be more attune at retrieving and transmitting the collected and shared memories. They can expand human capabilities and are central in almost all of our decisions.

In the second image, digital memory is represented the vacuum of space as a congested network or rigid highways. These digital highways are traversed and intersected by more organic sinuous forms. These organic forms harken back to the diverse nature of human memory. When human memories collide with the digital, they tend to distort and reflect these digital memories outwardly form their own perspective. There is an oversaturation of digital memory in the built environment, but by virtue of its transparency it does overstimulate us. We, in turn, have access to any information whenever and wherever we could ever need it.

The first image represents the transmission of a memory from a person’s head, to the digital dimension. The path that the man is on is one of past and present memories. This Third Eye is constantly sifting through the realm of thought to recollect and remember what is stored along the way. It represents the man himself, and his own view of what he believes is true and absolute. As memories leave the realm of thought into the digital, they become diluted into zeros and ones. As they leave the individual, they no longer belong solely to that person, but to all of us.

(43/50)

1797531033

Insomniac's Dreamcatcher

Something to REM-emeber

Waking up in the dark, trying to REM-ember where you were? Trying to REM-ember whether you were sleeping or living another secret life. Are you just a sleeping beauty or are you Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde?! Where is the reality? What are you trying to REM-ember!!?

To dream is to live another parallel reality that you are not aware of until you are awake. But who could say surely that one is fully awake? Maybe we are all still dreaming in another parallel reality!

Dreaming is another manifestation of reality, you can’t be exposed to two (three, four...or even more in some cases) realities except when in the medium between them. This medium is the stage between REM-embering (the dreams are taking place in the REM period) and remembering (the other reality is the case of remembering the every day’s incidents that creates the intellectual cognitive) What if you are an insomniac? And you don't have the luxury of REM-embering?

The REM state is the mechanism that connects us with reality; it is constantly running in the background, searching for the codes at lightning speed to metaphorically match to whatever is meaningful in the environment, and thus creating our perception of reality.

“It is a reality generator, accessing the templates that are the basis of meaning. (This is easily seen when people access memories that evoke strong emotions: rapid eye movements occur even when their eyes are open. We have much evidence of this on film.) It is active when we dream but also when we daydream. It is seen when people go into focused states of attention (trance) and when strong instincts are aroused. It is associated with hallucinations and hearing voices.” Why do we dream?- The expectation fulfilment theory of dreaming.

The design approach is to make an architectural intervention for these insomniacs, which collects dreams from sleepers who volunteer to share their dreams, to the main mind/heart of the intervention (virtual memory). The mind/heart feeds back the insomniacs with the collective dreams, to help them REM-embering some real memories.

Something to REM-emeber

Waking up in the dark, trying to REM-ember where you were? Trying to REM-ember whether you were sleeping or living another secret life. Are you just a sleeping beauty or are you Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde?! Where is the reality? What are you trying to REM-ember!!?

To dream is to live another parallel reality that you are not aware of until you are awake. But who could say surely that one is fully awake? Maybe we are all still dreaming in another parallel reality!

Dreaming is another manifestation of reality, you can’t be exposed to two (three, four...or even more in some cases) realities except when in the medium between them. This medium is the stage between REM-embering (the dreams are taking place in the REM period) and remembering (the other reality is the case of remembering the every day’s incidents that creates the intellectual cognitive) What if you are an insomniac? And you don't have the luxury of REM-embering?

The REM state is the mechanism that connects us with reality; it is constantly running in the background, searching for the codes at lightning speed to metaphorically match to whatever is meaningful in the environment, and thus creating our perception of reality.

“It is a reality generator, accessing the templates that are the basis of meaning. (This is easily seen when people access memories that evoke strong emotions: rapid eye movements occur even when their eyes are open. We have much evidence of this on film.) It is active when we dream but also when we daydream. It is seen when people go into focused states of attention (trance) and when strong instincts are aroused. It is associated with hallucinations and hearing voices.” Why do we dream?- The expectation fulfilment theory of dreaming.

The design approach is to make an architectural intervention for these insomniacs, which collects dreams from sleepers who volunteer to share their dreams, to the main mind/heart of the intervention (virtual memory). The mind/heart feeds back the insomniacs with the collective dreams, to help them REM-embering some real memories.

(44/50)

1815027535

WALD

‚Instead of searing memory into public consciousness (...) conventional memorials seal memory off from awareness altogether.’

James E. Young

Almost all of us share a common past, with subtle inequalities.

We learn to walk, speak, read and write, we ride our first bicycle, we fall in love for the first time.

We grow up, we age, we die.

All we need to reminisce, to think, is a trigger; a trigger that is not necessarily true, which source does not have to derive directly from us. Though, the memory will be utterly ours.

When we see a dog, we think of the dog.

When we see an accident, we think of the accident.

When we see a kiss, we think of the kiss.

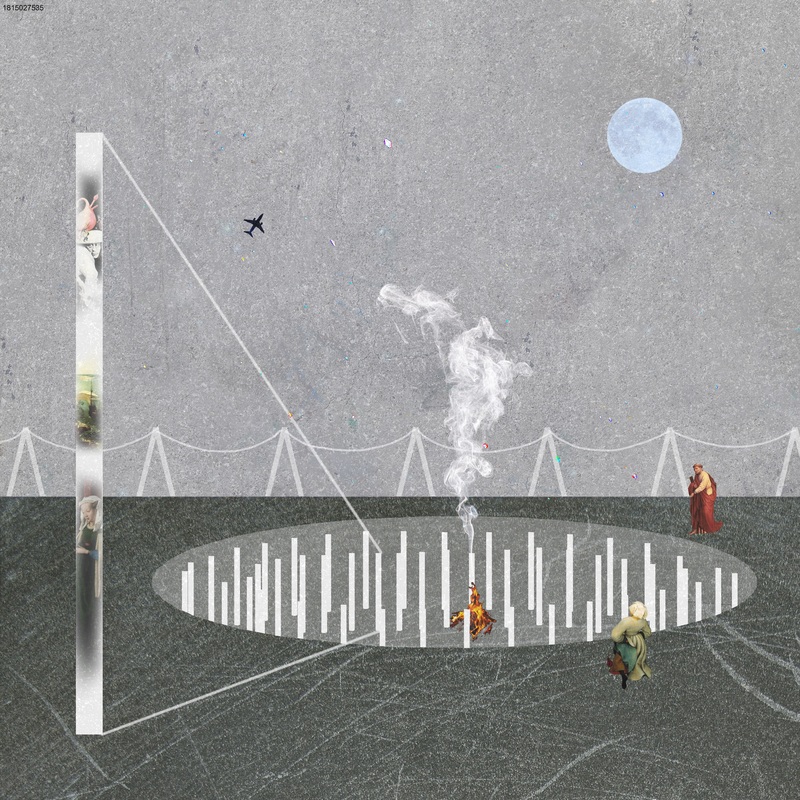

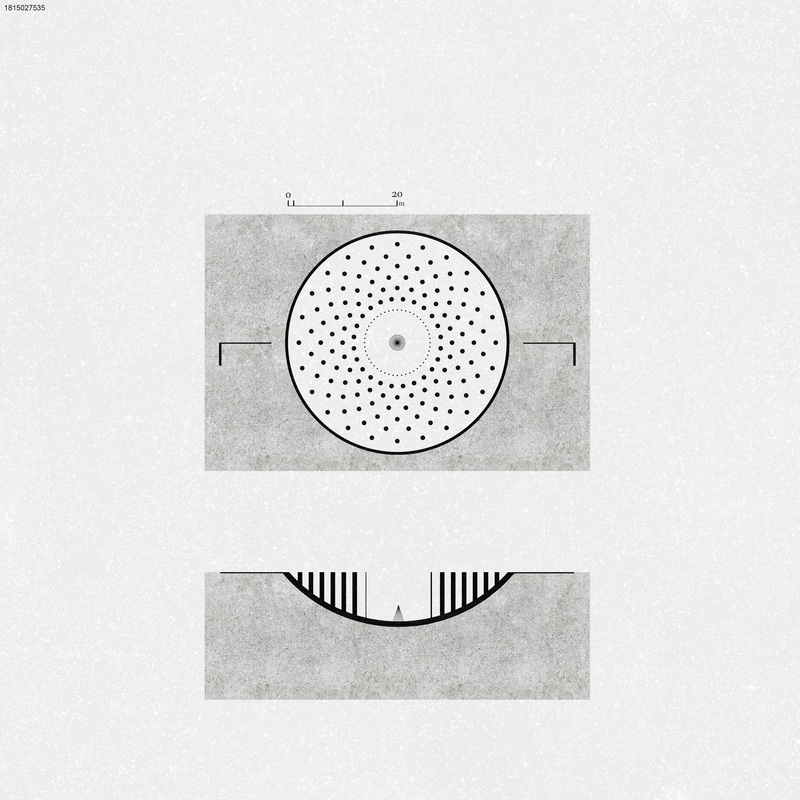

‚Wald’ is a proposition of a counter-monument, a memorial built entirely from real, tangible memories of its visitors, a memorial built inside one’s head.

A cavity in the land gently guides inside and down. Illuminated columns with a diameter of 80cm covered with circular screens serve as memory banks. They are constantly downloading data - photos, videos and audio recordings - from mobile devices nearby, transferring and displaying them onto themselves in a random, yet harmonious way. They create a ‚wald’, a dense forest of memories, facts, events and people.

Triggers, that activate hippocampus in search for one’s true,

individual memories.

There, near the oblate centre of the cavity, is a campfire, secluded from the rest of the area with a condensation of illuminated

columns with a diameter of 20cm, clear from picture and sound.

The aperture is narrow and one has to sidle in.

Around the campfire, people sit.

They interact: recall, talk, share.

The memory lives on.

‚Instead of searing memory into public consciousness (...) conventional memorials seal memory off from awareness altogether.’

James E. Young

Almost all of us share a common past, with subtle inequalities.

We learn to walk, speak, read and write, we ride our first bicycle, we fall in love for the first time.

We grow up, we age, we die.

All we need to reminisce, to think, is a trigger; a trigger that is not necessarily true, which source does not have to derive directly from us. Though, the memory will be utterly ours.

When we see a dog, we think of the dog.

When we see an accident, we think of the accident.

When we see a kiss, we think of the kiss.

‚Wald’ is a proposition of a counter-monument, a memorial built entirely from real, tangible memories of its visitors, a memorial built inside one’s head.

A cavity in the land gently guides inside and down. Illuminated columns with a diameter of 80cm covered with circular screens serve as memory banks. They are constantly downloading data - photos, videos and audio recordings - from mobile devices nearby, transferring and displaying them onto themselves in a random, yet harmonious way. They create a ‚wald’, a dense forest of memories, facts, events and people.

Triggers, that activate hippocampus in search for one’s true,

individual memories.

There, near the oblate centre of the cavity, is a campfire, secluded from the rest of the area with a condensation of illuminated

columns with a diameter of 20cm, clear from picture and sound.

The aperture is narrow and one has to sidle in.

Around the campfire, people sit.

They interact: recall, talk, share.

The memory lives on.

(45/50)

2043501489

Memories of home

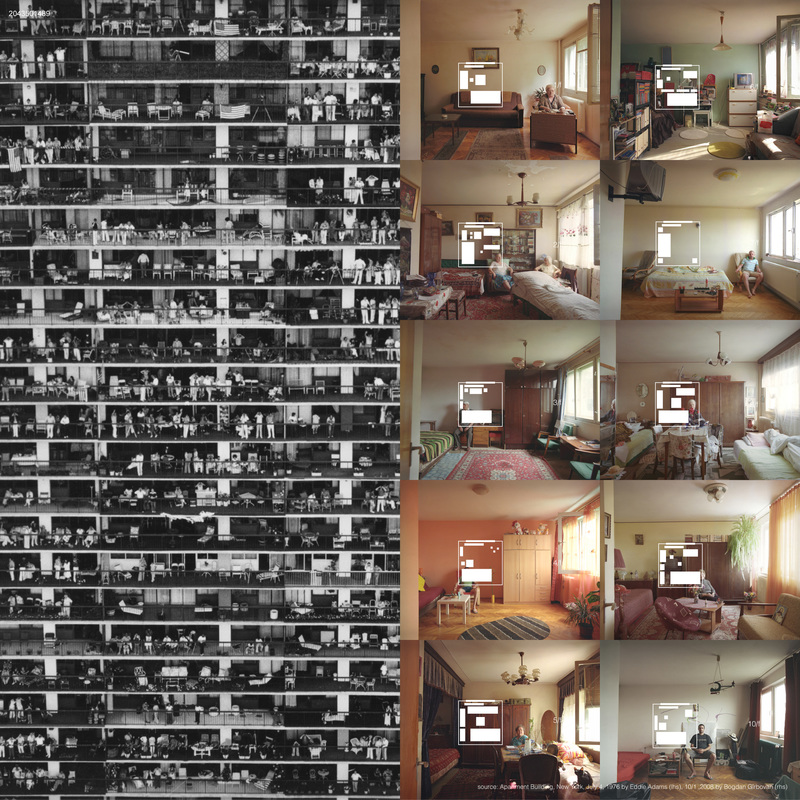

We spend a large proportion of our time in our house, meaning that a high proportion of memories are created or considered in a home. Each item in our home has its reason (function or memory) for being, we may describe our home as an interpretation of memory in physical state, somehow also implying our personality, values and experience, psychological state, interpretation of spatial perception.

New and old items or furniture keep moving in and out as times goes by, changing the layout or arrangement of our interior space, some items used for a while are thrown away, some remain for a long time but seldom be used and put at a corner, some specific places to put our most precious item or properties, some are abandoned because of moving home to another place.

We have our own way to organize our personal items, colour style of the furniture, items we choose to include, what remains now actually represent what really means to us, what we are interested in, that we are willing to live with them, surrounded by them, to look at them and touch them day by day and night by night.

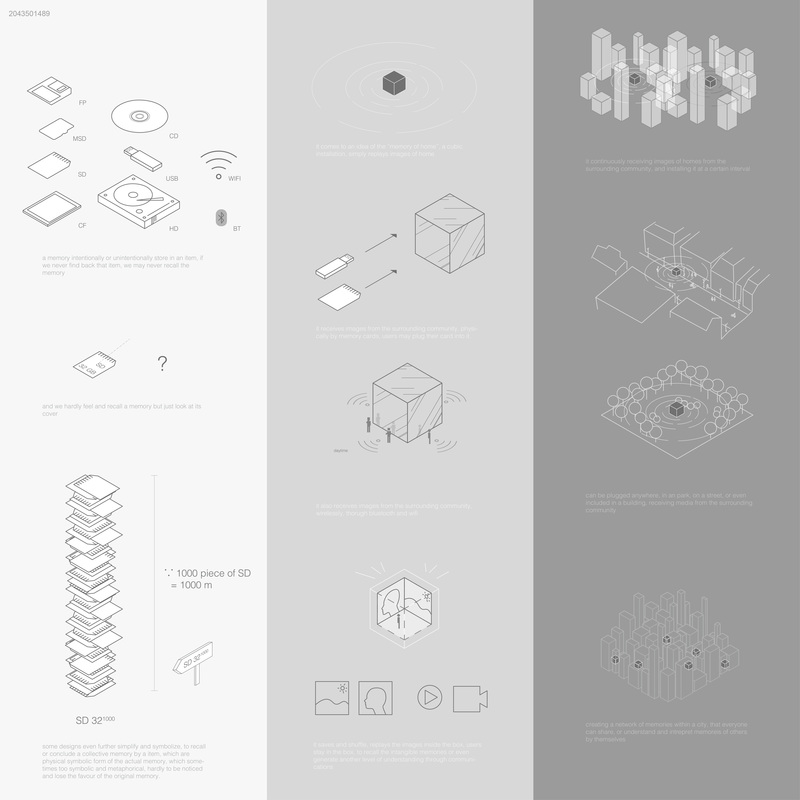

Some designs try to conclude a collective memory with a physical symbolic form of the actual memory, which sometimes are too symbolic and metaphorical, hardly to be noticed or understood, and lose the favour of the original memory.

It comes to an idea of the “memory of home”, a cubic installation, simply replays images of homes (images of how people occupy their flat or apartment or home), to recall the intangible memories or even generate another level of understanding, of how each person live with their memories. It receives images from the surrounding community, physically or wirelessly users may plug their recorded media by digital memory storage devices into it, it saves and shuffle, replays the images inside the box. The cube can be plugged anywhere, in an park, on a street, or even included in a building, receiving media from the surrounding community.

Finally our memory only stuck, stay at the third dimension base on we are just 3 dimensional mammals and we never truly or fully understand what memory is, understand it in all dimensions, we can just feel it by our own limited ways, our perspective recognition of memories, like being in the 3 dimensional cube “memory of home”, not unlimitedly, not infinitely.

We spend a large proportion of our time in our house, meaning that a high proportion of memories are created or considered in a home. Each item in our home has its reason (function or memory) for being, we may describe our home as an interpretation of memory in physical state, somehow also implying our personality, values and experience, psychological state, interpretation of spatial perception.

New and old items or furniture keep moving in and out as times goes by, changing the layout or arrangement of our interior space, some items used for a while are thrown away, some remain for a long time but seldom be used and put at a corner, some specific places to put our most precious item or properties, some are abandoned because of moving home to another place.

We have our own way to organize our personal items, colour style of the furniture, items we choose to include, what remains now actually represent what really means to us, what we are interested in, that we are willing to live with them, surrounded by them, to look at them and touch them day by day and night by night.

Some designs try to conclude a collective memory with a physical symbolic form of the actual memory, which sometimes are too symbolic and metaphorical, hardly to be noticed or understood, and lose the favour of the original memory.

It comes to an idea of the “memory of home”, a cubic installation, simply replays images of homes (images of how people occupy their flat or apartment or home), to recall the intangible memories or even generate another level of understanding, of how each person live with their memories. It receives images from the surrounding community, physically or wirelessly users may plug their recorded media by digital memory storage devices into it, it saves and shuffle, replays the images inside the box. The cube can be plugged anywhere, in an park, on a street, or even included in a building, receiving media from the surrounding community.

Finally our memory only stuck, stay at the third dimension base on we are just 3 dimensional mammals and we never truly or fully understand what memory is, understand it in all dimensions, we can just feel it by our own limited ways, our perspective recognition of memories, like being in the 3 dimensional cube “memory of home”, not unlimitedly, not infinitely.

(46/50)

2108343807

A possible path

Memory has always been one of the main aims and means of architecture. Even before the gigantic pyramids arose from the sands, mankind has used architecture as a way to defeat death and future oblivion. In contrast, we have always felt the necessity of a connection with the past, as the only possible way to give meaning to the places we inhabit. History of architecture is filled with examples of intellectual theft, reverence, unconscious plagiarism, homage and unconditional devotion.

But what is going to happen to these values, once memory won’t be such a fundamental part of our mental process?

Soon we are going to be so integrated with our computers that we will solely rely on them, in order to collect and organize the enormous quantities of data we are exposed to everyday.

Memory will become useless, nostalgic, analog, out of fashion.

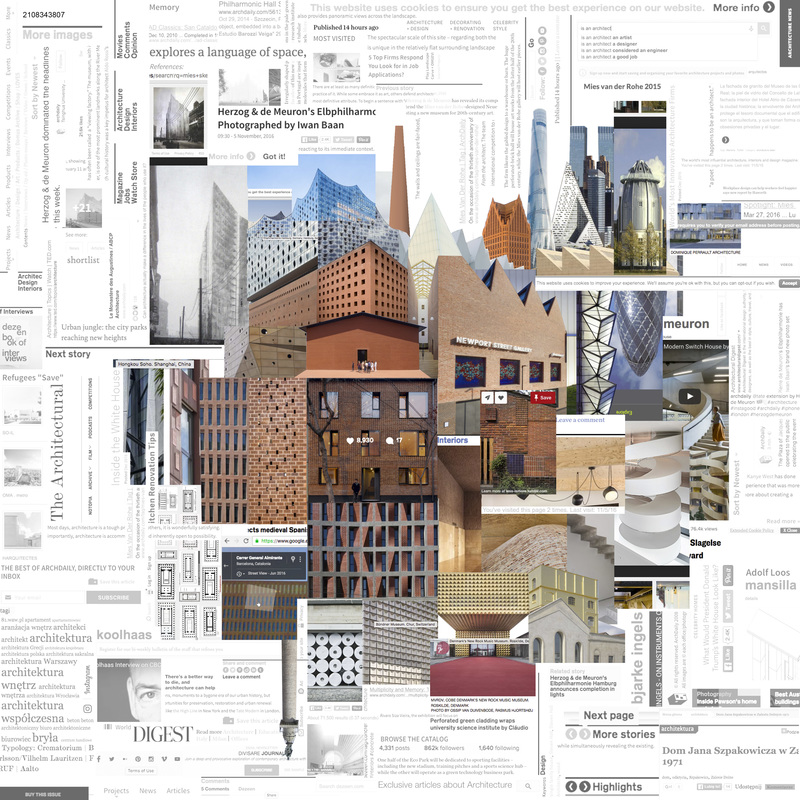

The most alarming symptom is that our culture is already merely reduced to image. Image is nowadays the only means through which we communicate architecture. Text is marginal, a disclaimer, a link. We don’t have time to read, analyze, comprehend. Shiny, high-contrast, desaturated, highly-modified - almost pornographic - pictures keep prevailing and being updated in a huge, invisible and tremendously fast archive, that we can access with the simple touch of our fingertips. Memory is losing its rituals of research, recognition and categorization, in favor of a holistic and confusing vision of the world. A vision that prefers serendipity over investigation, randomness over pertinence.

But even if we accept the inevitable transformation of the way we use our brains, how can we save meaningful architecture from this intellectual decay?

Luckly enough, memory works in a mysterious way and is still a precious tool that architects should never underestimate. A good architect could also just be a person with good memory - or with a good computer - who is capable of configuring his or her own recollections into a logical structure, to let something new come out of it.

Creativity usually comes from the collision of elements that would unlikely be connected by a computer, like the Japanese prints and Froebel gifts that inspired Frank Lloyd Wright’s unprecedented architectural language.

If computers will take over our capacity to catalogue and organize our memory, architects need to fight to keep their absolute privilege to discern meanings from the mass of information and their ability to create a meaningful system, a possible path.

Memory has always been one of the main aims and means of architecture. Even before the gigantic pyramids arose from the sands, mankind has used architecture as a way to defeat death and future oblivion. In contrast, we have always felt the necessity of a connection with the past, as the only possible way to give meaning to the places we inhabit. History of architecture is filled with examples of intellectual theft, reverence, unconscious plagiarism, homage and unconditional devotion.

But what is going to happen to these values, once memory won’t be such a fundamental part of our mental process?

Soon we are going to be so integrated with our computers that we will solely rely on them, in order to collect and organize the enormous quantities of data we are exposed to everyday.

Memory will become useless, nostalgic, analog, out of fashion.

The most alarming symptom is that our culture is already merely reduced to image. Image is nowadays the only means through which we communicate architecture. Text is marginal, a disclaimer, a link. We don’t have time to read, analyze, comprehend. Shiny, high-contrast, desaturated, highly-modified - almost pornographic - pictures keep prevailing and being updated in a huge, invisible and tremendously fast archive, that we can access with the simple touch of our fingertips. Memory is losing its rituals of research, recognition and categorization, in favor of a holistic and confusing vision of the world. A vision that prefers serendipity over investigation, randomness over pertinence.

But even if we accept the inevitable transformation of the way we use our brains, how can we save meaningful architecture from this intellectual decay?

Luckly enough, memory works in a mysterious way and is still a precious tool that architects should never underestimate. A good architect could also just be a person with good memory - or with a good computer - who is capable of configuring his or her own recollections into a logical structure, to let something new come out of it.

Creativity usually comes from the collision of elements that would unlikely be connected by a computer, like the Japanese prints and Froebel gifts that inspired Frank Lloyd Wright’s unprecedented architectural language.

If computers will take over our capacity to catalogue and organize our memory, architects need to fight to keep their absolute privilege to discern meanings from the mass of information and their ability to create a meaningful system, a possible path.

PAGE 1

<PREV PAGE 1 2 3 4 5 NEXT PAGE>

Questions: arch out loud team | 317.490.6142 | info@archoutloud.com